| | NEWS

HaRav Abdallah Somech of Raghdad

This article was originally published in 1994. It is here published online for the first time.

Part II

The first part told the extended story of the burial of HaRav Abdallah Somech and the persecution of the Jewish community that took place.

For Part I of this series click here.

Annulling a Libel

Miraculous stories about R' Abdallah Somech abounded not only after his death, but also during his lifetime.

In 5633, a strange episode took place, whose consequences were liable to have been grave.

A Jew named Mussa (Moshe) who had converted to Islam and lived outside of Baghdad, slandered a certain Jew and summoned him to court. The Jew swore that he had committed no crime and was vindicated. The angry apostate complained to the Wali and said:

"All the vows and oaths of the Jews are false. They always swear falsely in order to deceive their fellows. Every Yom Kippur they recite the Kol Nidrei prayer, in which they cancel the vows and oaths they are likely to utter during the forthcoming year."

The Wali was deeply influenced by this claim, and ordered R' Abdallah Somech, to explain the meaning of this "deceit." He dispatched some constables to bring him to his office.

When the gendarmes arrived in the Zeleika Bais Medrash, they found R' Abdallah Somech seated in the center of a semicircle, surrounded by thirty illustrious rabbis. R' Abdallah, whose face radiated majesty and sanctity, was engrossed in the study of a halachic work, and was oblivious to his surroundings. Whenever he was absorbed in a sefer, he would not lift his head until he had finished his study. At his right, sat his outstanding student, R' Nissim Levi Halevi.

The gendarmes turned to R' Nissim and asked him to notify the Rav that the Wali wished to see him immediately. R' Nissim whispered the message to the Rav, and wonder of wonders, the moment R' Abdallah lifted his head to listen to his student, the gendarmes disappeared. They returned to the Wali and told him:

"The man you asked us summon is not like other men. He resembles a Heavenly angel. It is impossible to bring him to you!"

The Wali reprimanded the gendarmes, and sent three others to the bais medrash of the Rav. They entered the bais medrash, stood beside the entrance to R' Abdallah's room, and asked his students to relay him the Wali's orders.

Hearing this, R' Abdallah rose, donned his robe and turban, and prepared to go to the Wali's office. His students also donned their robes and turbans and accompanied him. When passersby and shopkeepers saw their beloved Rav in the street, followed by scores of his illustrious disciples, they joined the procession. R' Abdallah Somech arrived at the Wali's office, accompanied by thousands of Jews.

The Wali was seated in his office, and awaited the arrival of the sage. When he saw thousands of Jews nearing, he thought that they had come to demonstrate, and ordered his gendarmes to disperse them. After the multitude had left, R' Abdallah Somech entered the Wali's office. A number of honorable rabbis, who also wore turbans, entered along with him.

When the Wali saw the image of the Rav, he realized that it had been wrong of him to summon so saintly and revered a person to his office for so minor and doubtful a claim.

The Wali, who was embarrassed to turn to the Rav and to investigate the charges of the apostate, asked one of the entourage, the wealthy and influential Moshe Tzadka, to explain the meaning of the Kol Nidrei prayer. R' Moshe asked for a machzor, and showed the governor the words: "All the vows and oaths...and the entire Nation is in error (beshgaga)." He then explained that on Yom Kippur, only vows which are made unwittingly, may be annulled. The phrase beshgaga does not pertain to monetary matters, but to other issues.

When the Wali heard Moshe Tzadka's explanation, he understood that the apostate had slandered the Jews falsely. He summoned the apostate and ordered that he be beaten in the Rav's presence. R' Abdallah, who did not know why the apostate was being punished, asked the Wali to pity the unfortunate man and to forgive him.

The Wali sent R' Abdallah home with much honor. After that incident, the Wali formed a deep friendship with him, and would visit him quite often, especially on Jewish holidays, and ask that he bless him with success.

Whoever Touches the Mountain Shall Perish

Alteif Ibn Raskaiya was a respected Moslem youth and a descendent of Mohammed. He served as a preacher in the courtyard of Yehoshua Kohen Godol, and composed a blasphemous lyric about the gaon R' Abdallah Somech.

Prior to his sermons in the courtyard of the Kohen, Alteif would roam the markets and close the shops. Whoever did not shut his shop then, would be labelled an infidel.

A contemporary reports:

"Throughout the day, Alteif would wander about, cursing and blaspheming. He composed a song about our beloved mentor, R' Abdallah Somech. Every night, he would read it in the coffee shops, and all the miscreants of the city would surround him and join in the raucous laughter and ridicule.

"One Thursday night, on the twenty-second of Adar, he told his followers to gather in the coffee shop, because he had composed a new lyric, which was much better than his first one. Soon the coffee shop was filled to capacity, and people had to stand in the street in order to hear the new song about Rabbenu.

"At one a.m., he began to sing, and his followers repeated the words of the song after him. That night, the Jews were ridiculed and mocked. The Arabs lingered in the coffee shop until five in the morning, listening to his song. When he finished, he rose, and made his audience vow, in Mohammed's name, to gather in the courtyard of the Kohen to listen to his sermon. Then he mounted the roof of the courtyard and summoned his followers to a prayer service.

"He climbed to the highest point in the tile roof and raised his voice. Suddenly, he slipped and toppled to the floor. Two Arabs picked him up and saw that he had fainted, and was in a state of confusion. They brought him home, and when he rose on Shabbos morning, he was unable to speak. Afterwards, his entire body became paralyzed, and he began to writhe in pain. The doctor who attended him said that he could not be healed. He died that night."

The more benevolent and righteous Moslems said that he had died so strange a death because he had disgraced R' Abdallah Somech.

The Ben Ish Chai

The Student of the Master

The gaon R' Abdallah Somech merited an illustrious disciple who illuminated the skies of world Jewry with his Torah and piety — the gaon, Rabbi Yosef Chaim, the Ben Ish Chai.

R' Yosef Chaim, the son of Eliyahu, the son of RM"Ch, was born in Baghdad in 5595 (1735). His great talents and lofty spiritual attributes were evident even when he was a youth. After attending a cheder, which in Baghdad is called an istat, he continued to study with his mother's brother, R' David Chai the son of Meir, the son of Yosef Nissim.

In 5608 he entered the Medrash Beit Zelka—a rabbinical academy—where his exhibited unusual talents. He excelled in his diligence, brilliance and remarkable memory. Soon he began to study with R' Abdallah Somech, the academy's founder and head.

After a number of years, R' Chaim left the bais medrash, and secluded himself in an attic which contained his huge library. There he studied day and night. When he was eighteen, he married Rachel, the daughter of the wealthy philanthropist, Yehuda Somech, a relative of R' Abdallah Somech. She helped him pursue his studies and advance in Torah.

In 5616, when he was twenty-one years old, he deliberated in halacha with R Chaim Palagi, the eldest of Izmir's rabbis. R' Chaim Palagi praised the Ben Ish Chai highly, and called him "chacham chein, richa uvar richa, mizera hamelucha, hachacham hashalem hadayan hametzuyan bar avhan uvar ori'an" (Chukas Chaim of R' Chaim Palagi, Izmir 5633, Choshen Mishpat, stanza 51).

In 5624, R' Chaim Palagi mentioned him again (in his introduction to Einei Kol Chai), saying: "See what our friend, R' Rechumai wrote about the [illustrious] Rav from Babylon Yosef Chaim, in his excellent book which appeared this year, Aderet Eliyahu."

His father, R' Eliyahu, died on the seventh of Elul, 5619 (1859). As soon as R' Yosef Chaim rose from his mourning, he replaced his father as Baghdad's darshan, and inherited the right—transmitted to him by his father and grandfather—to deliver the traditional sermons in Baghdad on a permanent basis. He occupied this position for fifty consecutive years, until his final day.

Official Darshan

It entailed reciting a steady sermon every Shabbos in Tzalat Lazgiri (the small synagogue) and delivering four other special sermons during the year. Although Tzalat Lazgiri was very large, it was called "the small synagogue" in order to distinguish it from the ancient synagogue, which was even larger.

His four other steady sermons were delivered on Shabbos Teshuva, Shabbos Zochor, Shabbos Hagodol and Shabbos Kallah, in Tzalat Lachbiri. On these occasions, all of the other preachers in the city would refrain from delivering sermons. As a result, all of Baghdad's Jews would flock to hear R' Yosef Chaim.

He was a very gifted speaker and his sermons had a tremendous impact on his audience and attracted hundreds of listeners. Until today, elders of Baghdad lovingly recall the sermons they merited to hear from him when they were young. His heartfelt words made deep impressions on his listeners. He enhanced his speeches with words of halacha and aggada, and with many educational stories and parables.

He recorded the innovations he made during these sermons in his many books. With every passing day, his renown grew greater. Soon he was accepted as the final posek of all the Jews of Iraq.

R' Chaim's home was open to the many callers who came to ask him halachic questions. As a mekubal and a saintly man, many sought his blessing and asked for rectification procedures (tikkunim) for their souls. He received everyone warmly and humbly, and expressed a deep desire to assist all who turned to him. His fame spread far and wide, and questions were sent to him from Jews all over the world.

R' Chai Yosef Chaim possessed a deep love for Eretz Yisroel, and generously supported the many emissaries who arrived in Iraq quite frequently in order to collect funds for the poor of their Land. The recommendations he gave were highly prized and had much value.

His recommendation for a certain charitable organization in Yerushalaim (see Shimru Mishpat Ve'Asu Tzedaka, page 13) is well-known. Under his influence, the famous philanthropist from Calcutta, Yosef Avraham Shalom donated all of his wealth in order to found Yeshivas Porat Yosef in Yerushalaim. Most of R' Yosef Chaim's books were published in Yerushalaim, in luxurious editions.

In 5629 (1869), he decided go up to Eretz Yisroel, the Land whose welfare he sought his entire life. The great dangers and difficulties of such a long journey did not deter him, and on Tuesday, the twenty-fifth of Nisan 5629, he left for Eretz Yisroel along with his brother R' Yechezkel.

They arrived in Damascus on the twelfth of Iyar, and from there continued to Yerushalaim, where they lodged in the home of their relative, R' Shlomo ben Yechezkel Yehuda. (Yechezkel Yehuda was founder of the famous Yehuda family which moved from Baghdad in 5616. He greatly aided the Jewish settlement in Eretz Yisroel, and was the founder of Yeshivas Chesed El in the old city of Yerushalaim.) The sages of Yerushalaim and her notables held a magnificent reception in honor of R' Yosef Chaim's arrival, and became deeply attached to him.

The elders of Baghdad relate that when they crossed the Syrian desert, R' Chaim told the Arab caravan leaders to cease travelling on Shabbos. When they encamped on Shabbos, a caravan of murderous thieves, bent on plunder, neared them. When they saw R' Chaim immersed in his studies, they fled. The entire party was saved on his merit.

Like his illustrious mentor, he performed wonders on the merit of his Torah learning and piety. Someone also spoke with him audaciously and sharply. He was banned from the Jewish community until he publicly apologized to the Ben Ish Chai.

His name was Yaakov Overmeyer, a Viennese Jew who had come to Baghdad to study French in the home of the Persian Abas Mirza, who was living in exile in Baghdad. Overmeyer, who sought to make a number of religious reforms in Baghdad, encountered the stern opposition of R' Yosef Chaim.

In 5636, Overmeyer wrote a number of letters to Hamaggid in which he dared to speak harshly against the Ben Ish Chai. The editor of Hamaggid, who did not know to whom the expressions were referring, published the letters verbatim, without investigating the matter.

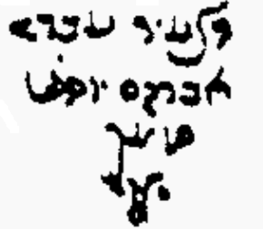

When those editions of the paper (7-11) arrived in Baghdad, the rabbis and notables of the city, led by R' Abdallah Somech, were shocked, and placed a ban on Overmeyer. The ban was read in all of the city's synagogues and was publicized in all of her streets. In addition, a sharp reply, published in the fourth edition of the paper, and signed by twenty-seven rabbis and dayanim of Baghdad, was prepared. They wrote a similar letter to the rabbis of Yerushalaim, which appeared in a special edition of Halevanon of the year 5636 (no.45).

They wrote: "Upon reading two or three (editions of Hamaggid) we were shaken to the core. The sacred and holy Rav and tzaddik has been trampled by an anonymous individual —a fool and an ignoramus—who accused him of wrongs he never perpetrated. It is R' Chaim, who, with his pleasant and interesting sermons, attracts [hundreds of Jews] each Shabbos. It is he who has returned many from sin. All of our brethren in the city shall follow in his light. They have banned this man who dares speak against our revered Rav. We have also heard that this ignoramus does not lay tefillin."

In the remainder of the letter, they refute all of Overmeyer's accusations, and praise the sermons of the Ben Ish Chai, saying that "everyone will testify and say that they are pure Torah and replete with mussar, yiras shomayim and derech eretz. R' Chaim has succeeded and has made a number of amendments, which were very necessary for the welfare of our city and which were willingly accepted by the entire congregation, forever after. No one opposes them in any way."

Not only the rabbis and dayanim of Baghdad, but also her communal leaders and philanthropists signed this letter. In this same edition of Hamaggid, the reply of the rabbis of Yerushalaim and Baghdad, signed by R' Avrohom Ashkenazi and R' Shalom Moshe Chai Gagin, appeared.

This letter was published on the seventeenth of Iyar 5636, and bitterly attacked Overmeyer. It said that he not only "blasphemed R' Chaim, but the Torah and its glory, as do all those who disgrace the sages of the Torah."

The ban placed on Yaakov Overmeyer and the sharp reaction of the rabbis of and notables of Baghdad bore fruit. At the request of the Chacham Bashi, all the synagogues in Baghdad refused to grant Overmeyer entry. Overmeyer sent letters of apology to Hamaggid and Halevanon, however their editors refused to publish them. At that time, his mother passed away, and the rabbis of Baghdad felt that he was being punished for having offended R' Yosef Chaim. No Jew agreed to pray in his home during the week of mourning. At last, he was compelled to go a bais din, and confess his sins, and to publicly beg R' Yosef Chaim's forgiveness.

|